Buenos Aires the bustling capital of Argentina, spread over the south bank of the Rio de la Plata, is a city of contrasts – of rich superhighways and narrow crooked streets, of plush apartments and suburban shanty towns, of wealth and poverty, of the famous and infamous.

Rapid suburban growth has changed the face of the city. Many historic structures have crumbled with age or demolished. Searching the suburbs of San Isidro to find Villa Milario is quite an adventure. It was the trysting place of Argentina’s distinguished writer Victoria Ocampo and the ageing Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore. For two months (November and December) in 1924 an old man of 63 years and a young lady of 34 mutually fuelled their creativity in each other’s company.

After Tagore won the Nobel Prize for Literature, Victoria took a great interest in his works. Her knowledge of English, Spanish and French gave her access to the best of literary works. She read Tagore’s “Gitanjali” and felt she could relate to the mystical yearnings and deep emotions expressed in his poems, and even said that she derived spiritual comfort from them.

Victoria was born into a rich family belonging to the high society of Buenos Aires. She was brought up in a very conservative atmosphere where women were not allowed to have a formal education. She was tutored by a French governess. But as a young girl, she travelled to Rome with her family and was allowed to attend lectures at the Sorbonne and the College de France, in the company of a chaperone. It made her eager to get better acquainted with the literary world.

By now, Tagore was a famous poet. He was invited to speak in different countries. On his travels to Latin America he fell severely ill on board the ship and had to disembark at Buenos Aires. He checked into the Hotel Plaza with his secretary and traveling companion Leonard Elmhurst. But because of Victoria’s great admiration for the poet, she offered to host them at Villa Milario in San Isidro, very close to her residence Villa Ocampo. It was situated in the middle of a beautiful compound with a cactus garden in the backyard, and a shady Tipa tree in the forecourt, under which Tagore met his visitors. From his balcony he had a view of the river. Victoria sold some of her jewellery to pay the rent for Villa Milario. Her personal servants attended Tagore’s every need.

Victoria herself spent the best part of the day with him. They even had their meals together. Leonard acted as the facilitator of their friendship as Victoria was rather shy. It was a rare friendship that stimulated the creative juices in both of them. Tagore cut short his visits to Peru and Mexico to bask in the ministrations of this lovely, intelligent muse.

Tagore had been a widower since the age of 41. However he had any number of women friends in Europe for his inspiration. But for the last seventeen years of his life Victoria became his muse. He considered her the most distinguished and attractive among all his female friends.

They parted in January 1925 when Tagore returned to Europe. Their epistolary romance was to continue until his death, except for two silent years from 1926 – 1928, when Victoria battled with her own private demons.

Their correspondence which was in English, revealed her devotion to him and his feelings for her. The letters were poignant with longing for emotional fulfilment. He taught her one word in Bengali ‘balobashi’ meaning love. Tagore immortalized her through his poems, never once mentioning her by name but by the Indian name ‘Vijaya’ which means victory. His book of poems ‘Purabi’ was dedicated to her. Yet though he idolized her, he refused to recognize her as an intellectual equal. This was truly frustrating for her.

They met for the last time in Paris in 1930, where she organized his first Art exhibition. He hoped that she would follow him to Shanthiniketan in India. But Victoria could not leave her lover Julian Martinez a diplomat, with whom she had a long standing relationship. Tagore had to be content with the arm chair she had presented him, which he had used in Milario. It had travelled with him through Europe and finally to Shanthiniketan. Many were the poems he was inspired to write from that arm chair.

On Tagore’s death in 1941, Victoria wrote his Obit essay.

“I guard everything I learnt from him,” she wrote, “So that I might live with it as long as my strength permits me.”

Victoria moved on from strength to strength. She was admired by musicians, writers and essayists. Many of them had visited her in San Isidro.

She aired her opinions fearlessly through her writing and essays. During World War II she supported and edited an anti-Nazi magazine ‘Lettres Francaises.’

In 1946, she was the only Argentinean to attend the Nuremberg trials.

In 1953, she was imprisoned for opposing the regime of Juan Domino Peron.

In 1961, on the birth centenary of Tagore, she organized a grand celebration in Buenos Aires. Her book “Tagore in the ravines of San Isidro” was well received.

Though Victoria lacked formal education, she established herself in the world of literature. She became a member of the Argentine Academy of Letters in 1976. Her home Villa Ocampo was used for cultural dialogues under the auspices of UNESCO. Most of her inherited wealth was spent on promoting Argentine’s culture.

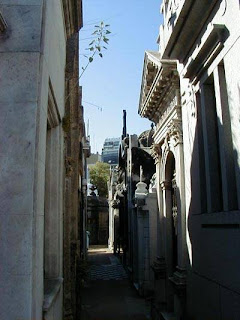

She died at the ripe old age of 88, on January 27th 1979. Her remains were interred at La Recoleta, the largest cemetery in Buenos Aires.

Rapid suburban growth has changed the face of the city. Many historic structures have crumbled with age or demolished. Searching the suburbs of San Isidro to find Villa Milario is quite an adventure. It was the trysting place of Argentina’s distinguished writer Victoria Ocampo and the ageing Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore. For two months (November and December) in 1924 an old man of 63 years and a young lady of 34 mutually fuelled their creativity in each other’s company.

After Tagore won the Nobel Prize for Literature, Victoria took a great interest in his works. Her knowledge of English, Spanish and French gave her access to the best of literary works. She read Tagore’s “Gitanjali” and felt she could relate to the mystical yearnings and deep emotions expressed in his poems, and even said that she derived spiritual comfort from them.

Victoria was born into a rich family belonging to the high society of Buenos Aires. She was brought up in a very conservative atmosphere where women were not allowed to have a formal education. She was tutored by a French governess. But as a young girl, she travelled to Rome with her family and was allowed to attend lectures at the Sorbonne and the College de France, in the company of a chaperone. It made her eager to get better acquainted with the literary world.

By now, Tagore was a famous poet. He was invited to speak in different countries. On his travels to Latin America he fell severely ill on board the ship and had to disembark at Buenos Aires. He checked into the Hotel Plaza with his secretary and traveling companion Leonard Elmhurst. But because of Victoria’s great admiration for the poet, she offered to host them at Villa Milario in San Isidro, very close to her residence Villa Ocampo. It was situated in the middle of a beautiful compound with a cactus garden in the backyard, and a shady Tipa tree in the forecourt, under which Tagore met his visitors. From his balcony he had a view of the river. Victoria sold some of her jewellery to pay the rent for Villa Milario. Her personal servants attended Tagore’s every need.

Victoria herself spent the best part of the day with him. They even had their meals together. Leonard acted as the facilitator of their friendship as Victoria was rather shy. It was a rare friendship that stimulated the creative juices in both of them. Tagore cut short his visits to Peru and Mexico to bask in the ministrations of this lovely, intelligent muse.

Tagore had been a widower since the age of 41. However he had any number of women friends in Europe for his inspiration. But for the last seventeen years of his life Victoria became his muse. He considered her the most distinguished and attractive among all his female friends.

They parted in January 1925 when Tagore returned to Europe. Their epistolary romance was to continue until his death, except for two silent years from 1926 – 1928, when Victoria battled with her own private demons.

Their correspondence which was in English, revealed her devotion to him and his feelings for her. The letters were poignant with longing for emotional fulfilment. He taught her one word in Bengali ‘balobashi’ meaning love. Tagore immortalized her through his poems, never once mentioning her by name but by the Indian name ‘Vijaya’ which means victory. His book of poems ‘Purabi’ was dedicated to her. Yet though he idolized her, he refused to recognize her as an intellectual equal. This was truly frustrating for her.

They met for the last time in Paris in 1930, where she organized his first Art exhibition. He hoped that she would follow him to Shanthiniketan in India. But Victoria could not leave her lover Julian Martinez a diplomat, with whom she had a long standing relationship. Tagore had to be content with the arm chair she had presented him, which he had used in Milario. It had travelled with him through Europe and finally to Shanthiniketan. Many were the poems he was inspired to write from that arm chair.

On Tagore’s death in 1941, Victoria wrote his Obit essay.

“I guard everything I learnt from him,” she wrote, “So that I might live with it as long as my strength permits me.”

Victoria moved on from strength to strength. She was admired by musicians, writers and essayists. Many of them had visited her in San Isidro.

She aired her opinions fearlessly through her writing and essays. During World War II she supported and edited an anti-Nazi magazine ‘Lettres Francaises.’

In 1946, she was the only Argentinean to attend the Nuremberg trials.

In 1953, she was imprisoned for opposing the regime of Juan Domino Peron.

In 1961, on the birth centenary of Tagore, she organized a grand celebration in Buenos Aires. Her book “Tagore in the ravines of San Isidro” was well received.

Though Victoria lacked formal education, she established herself in the world of literature. She became a member of the Argentine Academy of Letters in 1976. Her home Villa Ocampo was used for cultural dialogues under the auspices of UNESCO. Most of her inherited wealth was spent on promoting Argentine’s culture.

She died at the ripe old age of 88, on January 27th 1979. Her remains were interred at La Recoleta, the largest cemetery in Buenos Aires.